Talking about the future leaves you open to all kinds of challenge, not to mention fun-poking. All future-gazing attempts are wrong in some respect, and some are so off-base as to be hilarious.

Geoffrey Hoyle’s 1972 children’s book Living in the Future predicted that we’d all be wearing jumpsuits by now. He also thought we’d have more leisure time – and the less said about that the better. On the other hand, he did successfully predict video phones and online shopping. More about this curious book can be found in a BBC article here.

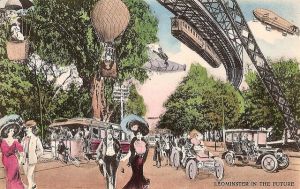

French artist Villemard has provided the perfect opener for my presentations about this project, with his visions of the year 2000 produced between 1899 and 1910. Again there is a mixture of weirdness and dodgy fashions among which are a few spot-on predictions, not to mention things we wish would happen (who wouldn’t want monorails and flying policemen?).

Exactly the same can be said of this 1970s vision of the future: terrifying fashions, startlingly familiar architecture, cool personal flying machines.

So why would anyone do it? I’ve discovered that anyone involved in futures work tends to have a well-rehearsed answer to this. And although I’m relatively new to futures work, a layman really, here’s mine:

Scenario planning provides a structured way in which to look at the future. Without this we – our organisations – are subject to whims and prey to every sensationalist headline that crosses the desks of our senior managers. To my mind, its strength lies in its breadth. It is a process that doesn’t consider different trends in isolation (MOOCs spring to mind here) but looks at how different changes will work together at the national and even global level. Of course with so many variables involved we’ll inevitably get it wrong sometimes, but I believe the discipline of systems-thinking it engenders makes it worthwhile.

It also holds up the mirror to the present. Here are some ways the future could go- how do you feel about this? What are we and our partners and stakeholders doing to further any particular future, either purposely or inadvertently? This proved useful in so many ways within this project; for UNITE’s board in articulating and challenging its most fundamental assumptions, and for the students we worked with who fought strongly for a rounded student experience once they saw it could be under threat.

So future-gazing can be an intensely practical activity, despite its dire track record on the sartorial front. It holds up a vision to which people respond, either positively or negatively, and automatically this creates action, it creates change.

Next week we’ll be blogging extended material from our scenarios; lots of it will be wrong, but that’s ok and now you know why. And besides, in the words of John Feffer, ‘being a futurologist means never having to say you’re sorry’.

Jenny Shaw